by Edmund Frazier Myer

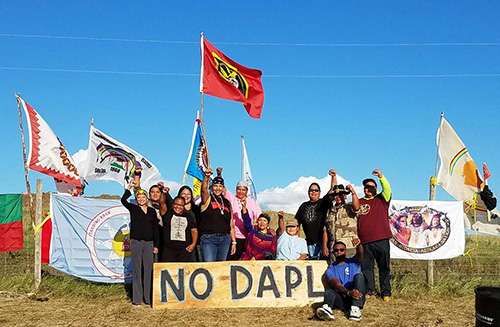

Angela Picard, WSU doctoral student, and Nez Perce tribal member, heard about the pipeline on social media. Looking further into the issue, and seeing that it was being compared to the Keystone pipeline, she began to have a genuine concern, said Picard. Cougs are joining tribes from across the nation in rallying to show support for the Standing Rock Sioux and their protest against the Dakota Access Pipeline.

In August, Picard went to North Dakota for three days to transport donations from local tribes and organizations. She explained while in North Dakota she played stickgame, and participated in cultural ceremonies such as the water ceremony, handshake ceremony, and story-telling.

Her experience there was “surreal,” Picard said. “So, many Natives from all across the country gathering for one common cause.”

Picard and others already attended two rallies in Lapwai, ID, and plan to attend one in Boise. They are also getting ready to take more vans full of donations to North Dakota.

The pipeline is designed to transport crude-oil across four states. Although it won’t be constructed directly on the reservation, it’s designed to be built on roughly 1000 acres of land that borders the Standing Rock Reservation and underneath their only water source.

Around the middle of August, as Native Americans gathered to peacefully protest, the “water protectors” were confronted by private security companies. The group, and even reporters, were being sprayed with pepper-spray, attacked by dogs, and arrested as construction crews began bulldozing at the site. On Sept. 16 President Obama announced a temporary halt on construction.

Another WSU student planning to travel to Standing Rock is Samantha Reyes, enrolled Turtle Mountain Chippewa (ND). Reyes explained after seeing what’s going on over there, she felt hurt.

The oil pipeline could potentially contaminate the main water source of the tribe, but the issue is bigger than that. That source of water happens to be the Missouri River, which is the same river millions of others rely on. This causes Reyes to wonder why others aren’t raising more concern.“You kind of feel helpless being all the way over here,” Reyes said. “It’s not your particular tribe but it’s still your people, so you feel it.”

She said, “It’s seen as the Native phenomenon, but it’s affecting a lot of people.”

Reyes is doing what she can here on campus to help the cause. In addition to helping with a food-drive and fundraiser on campus, she was part of a protest on Terrell Mall, where in order to create awareness, Native American students held up signs and did traditional dances.

Reyes explained that she’s receiving a lot of support from the community, especially the Latino community.

“It kind of made it more close-knit, so I feel like we were pretty well supported by the community here,” Reyes said.

Mykel Johnson, sophomore student, and 2016-17 Miss Pah-Loots-Pu, said, “It’s not just them standing up to these big corporations, but it’s us fighting for what we have left, fighting for the rights we’ve always wanted.”

Johnson understands that the pipeline would create jobs for individuals hoping to get into the oil industry, but Johnson, as well as many other Native Americans, view it differently.

“This is where these people have been forever, their family, their parents, their grandparents. I just feel bad for the future generations,” Johnson said. “You have people who fight for constitutional rights but you don’t have people necessarily fighting for these treaty rights.”

“It’s heartbreaking because if right now at this point in time we can’t be recognized as a sovereign nation; if in 2016 we can’t be recognized as our own entity or somebody who the United States government made a contract with, what does that say for our children’s children?” Johnson asked.